Composing Appalachia

This week was busy and productive. I was rapping up a set of six pieces for guitar, and I began the first of a series of arrangements of Appalachian folksongs for voice and cello for a duo I know. I want to talk a little bit about the origin and genesis of this project.

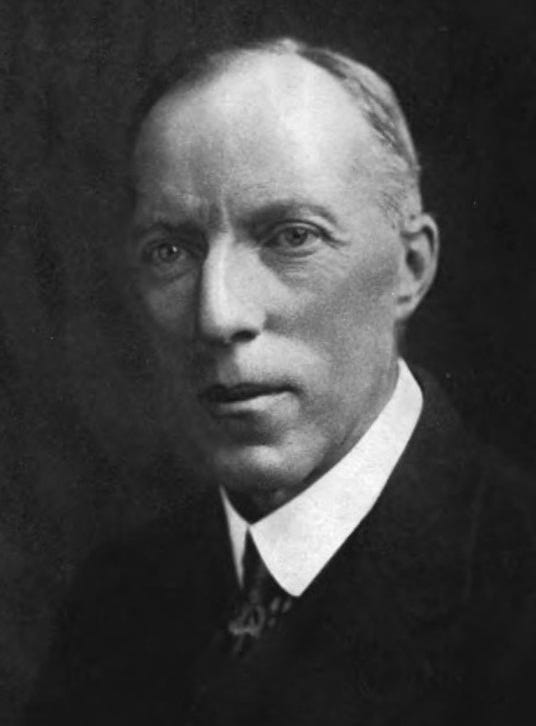

When I was an undergraduate composition major, I spent a good bit of time perusing the musicology section of the library at the North Carolina School for the Arts. I happened upon an interesting volume entitled, ‘English Folksongs of the Southern Appalachians,” by Cecil Sharp. Being from Appalachia myself, this piqued my interest. As I went through the volume, I was struck by the fact that I knew little to nothing of any of this music. I knew some of the lyrics of the various ballads and songs from English lit classes, but nothing of the tunes or songs themselves. I realized that an entire culture had once existed in my part of the woods that was for all practical purposes dead. It had been replaced with various forms of popular music that was carefully marketed and created for mass audiences. In fact, the advent of the technologies that would create this new paradigm for the transmission of music was in its infancy when Cecil Sharp undertook his collecting of folksongs both in the British Isles and America. He realized that oral folk culture was not going to survive the technological revolutions underway. And, he was correct.

Cecil Sharp was born in England in 1859. Although educated in music at home, he didn’t pursue music until somewhat later in life after a brief career as a lawyer. He emigrated to Australia and worked for a time as an to one of the chief justices of Australia. He then returned to England to pursue music fulltime. Around 1904, he met a women named Emma Overd, a barely literate agricultural worker. He was fascinated by her singing and particularly by the songs she sang, and as a consequence make it his calling to go out into the countryside and document music that had been orally transmitted.

Sharp was not the only person pursuing this. At about the same time, Bela Bartok and Kodaly were doing similar research in Hungary and Transylvania. They were themselves preceded by folksong revivals earlier in the 19th century by German musicologists and also by nationalist composers such as Dvorak, Smetana, and others. Nor was Sharp alone in England. Two other young composers, Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams were also in the field as it were, collecting hundreds of folksongs. All in all Sharp collected over 4,000 songs, a quarter of which were collected in Appalachia. I will have more to say about Sharp at a later time. His work is not without criticism, but without it, an entire culture would have been irretrievably lost.

The particular song I am working on at present, and have almost completed, is a version of the famous border ballad, Lord Randall. One well known version from the Anglo-Scottish border goes like this:

"Oh where ha'e ye been, Lord Randall my son?

O where ha'e ye been, my handsome young man?"

"I ha'e been to the wild wood: mother, make my bed soon,

For I’m weary wi' hunting, and fain wald lie down."

"Where gat ye your dinner, Lord Randall my son?

Where gat ye your dinner, my handsome young man?"

"I dined wi' my true love; mother, make my bed soon, For I'm weary wi' hunting, and fain wald lie down."

"What gat ye to your dinner, Lord Randall my son?

What gat ye to your dinner, my handsome young man?"

"I gat eels boiled in broo: mother, make my bed soon,

For I'm weary wi' hunting, and fain wald lie down."

"What became of your bloodhounds, Lord Randall my son?

What became of your bloodhounds, my handsome young man?"

"O they swelled and they died: mother, make my bed soon,

for I'm weary wi' hunting, and fain wald lie down."

"O I fear ye are poisoned, Lord Randall my son!

O I fear ye are poisoned, my handsome young man!"

"O yes, I am poisoned: mother, make my bed soon,

For I'm sick at the heart, and I fain wald lie down."

The various Appalachian versions differ quite a bit from the original, yet the structure of the narrative remains the same. Instead of Lord Randall, the young man is named Jimmy Randolph. Both are poisoned. In the earlier version, the reason for his poisoning is not revealed, but in the Appalachian version, he is poisoned by his lover. Since some of the transcriptions of the songs found in Appalachia did not always contain all of the lyrics, I did have to do some textural editing. The version I am using goes like this:

What you will to your father, Jimmy Randolph my son? What you will to your father, my oldest, dearest son? My horses, my buggies, Mother, make my bed soon, For I am sick hearted and I want to lie down. What will to your brothers, Jimmy Randolph my son What will to you brothers, my oldest, dearest son? My mules and my wagons, Mother, make my bed soon, For I am sick hearted and I want to lie down. What will to your sisters, Jimmy Randolph my son What will to you sisters, my oldest, dearest son? My gold and my silver, Mother, make my bed soon, For I am sick hearted and I want to lie down. What will to your mother, Jimmy Randolph my son What will to you mother, my oldest, dearest son? My lands and my houses, Mother, make my bed soon, For I am sick hearted and I want to lie down. What will to your sweetheart, Jimmy Randolph my son What will to you sweetheart, my oldest, dearest son? Ten thousand weights of brimstone to burn her bones browm For she was the cause of my lying down.

The tune I chose for this arrangement was sung by Dora Shelton at Allanstand, North Carolina on August 2, 1916. Most folksongs often employ pentatonic or hexatonic scales. This version uses a pentatonic scale, omitting the 4th and 7th scale degrees of the our normal major scale.

At present I have selected three folksongs for the voice/cello duo. I will probably add more later. There is also one song I’m looking at for a possible choral setting. Just how far I will explore this collection I’m not sure. It’s very rich in content and expression, and we’ll just have to see.

In other news, I began the process of building a blog. As I suggested in my New Year’s newsletter, I would like to produce this as a kind short form communication that focuses on what I’m currently working on, along with some brief discussions of the creative life in general. I would like to leave the more academic side of things to a longer form blog, probably on a monthly basis rather than weekly. I will be building that blog on Wordpress.

There are two other projects I am developing. One is a set of courses I will most likely put up on Skillshare. I am developing courses on elementary harmony, basic counterpoint, orchestration, and beginning adult piano. This is obviously a long term project, and I will keep you updated as to its progress. The other is the possibility of a podcast. This is a little uncertain at the moment, but I am sending out feelers to possible interlocutors to see if there would be some interest. I’m not sure which platforms I will post to, but I will almost certainly use Substack in some capacity.

That about raps up the week. As I said, it’s been a busy one, not including a sick cat. I wish you all a good week, and will talk with you again soon!

Roundup: